– by Polly

My father is a wonderful person. This post is for him.

This year I met my father properly for the first time. I’m thirty years old.

I had met him once before, when I was about 19 and ventured round to his home. I was drunk, confused and hoping to ease my pain. He was happy to see me then, of course, but I was belligerent and sad and didn’t know how to handle the situation with any grace. I subsequently disappeared off his radar for a decade. We spoke a handful of times on the phone and he sent strange Christmas presents and cards on my birthday. I went to university, lived in a couple of different countries, and carried on with my life, always wondering about when my father’s legacy would be my own. He has schizophrenia, you see.

From the age at which I could conceptualize the ramifications of this illness, I have feared it. I have feared that at some unknown point in my life, I would become sick. I have feared that I already had it and was so out of it as to be completely unaware of it, and of course, I have feared it being something I pass on to my own children. My mother’s family tried desperately to shield me from it by shutting my father out until I could decide for myself whether or not I wanted to meet him. My grandmother was hoping my mother would tell me he was dead.

Their protective zeal, predictably, led me to be far more fearful than was appropriate or necessary. My curiosity about what it meant for my father to be afflicted by this illness, about how he lived his life and interacted with people, and about how he acted, was coupled with shame. Shame about the fact that I had no father figure present in my life, or rather that he was “defective” in this way, though I had no concrete examples of his behavior other than those I imagined. As I grew older, I also started to feel angry towards my maternal side for cutting him from my life. Could they not have made the effort to include him in some way? Had he hurt me? Why was he being punished?

Schizophrenia haunted my life from early teenage until very recently, when I met my father.

Today, he is a quiet man, with sadness and worry in his eyes. He is tired, all the time, from his medication. His words sometimes slur. He was also recently diagnosed with prostate cancer, and will, from today, be undergoing radiotherapy. Nonetheless, he smiles at me and my family and asks about my life. He is capable of so much. I still haven’t met him enough times to recognize myself in his face, but I always look.

I cannot know exactly how his behavior would have been when I was an infant. I cannot know how my mother and grandmother felt about his presence in my life, given that he was prone to unpredictability. I cannot know anything more than I do about that time, because I have asked as many questions as I could, and I no longer dwell on the decades that I missed being my father’s friend. I no longer fear schizophrenia. But could I have been spared the angst, fear, and shame if I had known my father sooner, and learned that his disease was manageable at times, less manageable at others? If I had seen first hand that he could function in society as was expected, if not always, then some of the time? Could I have bypassed the mental pain of having a missing parent and the burning curiosity about him and his life? All the time I spent wondering “does he look like me? Do we share the same mannerisms? Could he make me laugh?”

Children… deserve us to be courageous on their behalf, to show them there is nothing to be afraid of, only demons to be outed and myths to be dispelled.

I feel like I was burdened with something that could have been avoided. I feel like the strategy my family used (I know they only knew what they knew at the time), a strategy aimed at caring for and “protecting” me, backfired. My family was honest with me, but their courage was lacking. Children deserve our courage. They deserve the best version of us, questioning the current norms, bucking the trends and getting to the heart of the matter. They deserve us to be courageous on their behalf, to show them there is nothing to be afraid of, only demons to be outed and myths to be dispelled.

I hope that I can show my daughter the honesty my family showed me, and I hope that I can combine that honesty with fearlessness in the face of mental illness, wherever we may encounter it. Hiding from or denying mental illness merely perpetuates a needless taboo and does not encourage curiosity or openness. An uncle of mine once told me “we all have a diagnosis”, and I am of the belief that everyone has quirks and idiosyncrasies that could potentially be diagnosed and medicated. Mental health is a spectrum.

It is not my job to protect my daughter from other people by shielding her from them; it is my job to provide her with the information she needs to be able to interact with others and learn about them, on her own terms, but with my help, if she requests it. One of the biggest gifts I believe I can give her is confidence in her own heritage and a clear insight into her past.

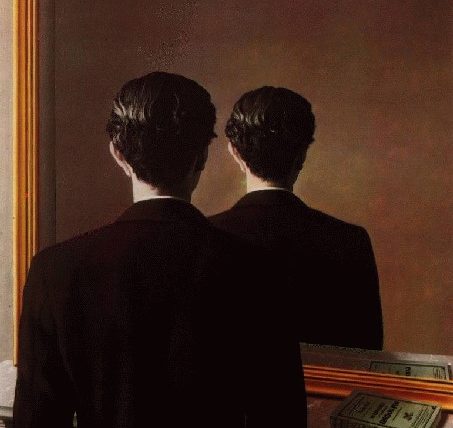

As for me: I want to continue to get to know the man behind the mask of mental illness. My father’s drugs take more from him than I would like. I see his spirit in there, and at times I feel like we are connecting. I am thankful that I have the chance to see that his illness does not define him, and will not be the only thing that people remember of him.

This is a beautiful and moving story of your relationship with your family. It has such an important lesson.

Thank you Tiki! It was very cathartic to write about it.

Wow Polly -a difficult experience for you, beautifully written and expressed! Your father and children will benefit from your courage, insight and compassion!